By Zahra Hankir

In August 2013, Egyptian security forces raided a sit-in camp in Cairo filled with hundreds of protesters supporting ousted President Mohamed Morsi. According to Human Rights Watch, the ensuing clashes between the army and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood at Raba’a Square left at least 817 civilians dead.

It’s near-impossible to imagine — let alone depict — the chaos and hatred that must have permeated the air in the weeks that led up to that horrific massacre. And yet, Mohamed Diab, the talented director of “Eshtebak” (“Clash”), somehow manages to do just that, in a superb 97-minute film that’s expertly shot in and from one location: the back of a run-down police van.

We’re first introduced to journalists who work with the Associated Press, shoved into the back of the van by the police for simply doing their job. They’re soon joined by civilians opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood, and then by civilians who support the Muslim Brotherhood, and then by an ambivalent policeman.

The group is something of a microcosm of Egyptian society, and its interactions serve as the perfect manifestation of turmoil in the country, some two years after former President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. While they’re all supporters of different factions, or none at all, the prisoners share that they’re taken in without reason and subjected to hours of inhumane treatment. But they refuse to set aside their differences for a large portion of the film, accusing each other of being American agents, Islamic terrorists, hedonists or state sympathisers.

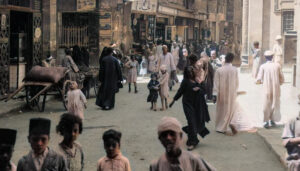

As the van navigates the narrow, windy streets of Cairo’s neighbourhoods without direction or destination, we witness sheer chaos through its windows. The police indiscriminately shoot at the crowds, showering them with tear gas. A lieutenant is gunned down. The perpetrator is beaten to death and left in a pool of blood on the road.

Meanwhile, the frustration of the passengers is near-excruciating to watch. The back of the van becomes increasingly claustrophobic and manic: the prisoners must urinate in a small water bottle, there’s no food or water and the heat of the summer sun suffocates them.

“Clash” is, quite crucially, not without levity. There’s a homeless man pretending to be a thug, an aspiring DJ who’s worried about how his gelled-back hair looks and a Muslim Brotherhood supporter who sings a Nancy Ajram song shortly after sustaining a bloody injury. A young girl’s veil slips off her head for a few moments, and she exchanges tender eye contact with a boy her age whose family is at the other end of the political spectrum. These endearing moments allow the prisoners to ultimately connect with one another, and to recognise that they’re all experiencing the same injustices forced upon them by the brutal security forces.

What’s most important about this electric film, though, is that it remains politically neutral. No one (excluding, perhaps, the children and a homeless man) is depicted as innocent. Everyone has been deceived or brainwashed by someone. At one point, we’re even tempted to sympathise with a police officer, who argues he had no choice but to serve the state apparatus. Each prisoner is a victim of his or her own circumstances and of the “state,” rather than their bigoted beliefs.

Diab’s nuanced approach is distinct and clearly intentional. In an interview with the BBC’s Hard Talk in October, he said that “Clash” “praises anti-hysteria and anti-division; there’s no more bigger and more important message now, in today’s Egypt. I’m trying to humanize the enemy.”

“Clash” deserves all the praise that’s being heaped upon it: the film was an official selection at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, and it represented Egypt in the category of Best Foreign-Language film at the prestigious BFI London Film Festival. It’s also received multiple awards at global film festivals including the Critics Prize at the Mediterranean Film Festival of Brussels and the Audience Prize at the International Film Festival of Kerala. The movie was screened in Egyptian theatres in summer last year, and is currently showing at select cinemas across the United Kingdom.

“Clash” is a fine addition to films documenting the Egyptian revolution and its aftermath, including Jehane Noujaim’s “The Square” and Fredrik Stanton’s “Uprising.” It’s a wonder to think this is only Diab’s second film. His first, “Cairo 678,” ambitiously focused on sexual harassment in Egypt and was also highly acclaimed.

For now, it’s clear that the New York Film Academy-educated director is focusing his creative energies on his home country and the deep divisions between its people. And we’re better off for it.