*Interview by Mia Jankowicz. Photographs by Virginie Nguyen.

**This post originally appeared on ArtTerritories.

Mada Masr is an online bilingual Egyptian newspaper founded by Lina Attalah and a team of journalists in June 2013. Its origins lie in the major Egyptian Arabic language newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm (AMAY)’s English language edition, Egypt Independent (EI) and its short-lived print edition. Despite strong readership of EI’s progressive, nonpartisan investigative journalism and strong cultural writing, AMAY announced the closure of the EI print edition in Spring 2013, firing 25 journalists and retaining only a few staff to produce English translations of AMAY’s Arabic content, effectively shutting down EI as we knew it. Out of a smaller group of ex-EI staff, however, Attalah has formed Mada Masr as an independent entity, which launched on 28th June 2013.

In this interview I look at what particularly marks out Mada Masr in the Egyptian media and cultural landscape at this point. The conditions Mada has experienced are not coincidental in a news media scene leveraged largely by strong partisan interests and built on highly sedimented institutional positions; yet what Mada has become is highly exceptional. This interview was conducted over two sessions in July and October 2013; firstly, soon after Mohamed Morsi’s ouster and Mada’s founding; secondly after an exhausting summer including the massacre at Rabaa al-Adaweya.

In an article published in EI’s final issue in April 2013, The Triumph of Practice, Lina Attalah described the closure of EI and the issues it raises about autonomy and self-reflexivity in the Egyptian media picture. This interview begins by attempting to further those questions.

Mia: In The Triumph of Practice, you outline the rationale given by AMAY’s directors for closing EI as it was. They gave financial reasons, in relation to Egypt’s economic crisis, as well as emphasized the need to explore digital rather than print – all the while glossing over the firing of 25 journalists. You, in turn, argued that the financial non-viability was unfairly laid on EI, when this is a management failure, not a journalistic one. What do you think this episode says about the Egyptian media establishment?

Lina: The Egyptian media establishment is growing increasingly limiting to independent media practice and practitioners. They have been doing so through a series of policies and directions that haven’t come out of research or even the desire to find new robust solutions in response to growing economic challenges. There is only a process of reproducing these challenges. For example, Egyptian media prints in order to make money, because web advertising doesn’t pay the bills, it’s actually the print ads that do. That’s why AMAY still keeps printing, and that’s why EI started printing. And then in defending itself, the institution uses a relic of the practice they let go of. So, to the world, they say they ended the print edition of EI and kept the website in line with the world going digital, when in reality they downsized the whole operation and let go of the team that produces content for both the website and the print edition. We have initially said that we should invest in the web as much as we can rather than divert and go print. But they never listened.

Mia: You say it defends itself, so what is the threat?

Lina: Every financial or economic argument has a political depth to it. And the political depth here is that if EI was a ‘fluffier’ paper, that serviced the lifestyle of the wealthy elites by investing in fashion, eateries, and travel journalism, which I don’t mind by the way, it might have survived. It might also have survived if its political line was more in sync with the editorial policies of AMAY, such as compromising some coverage on institutions shaped and produced by mainstream, both corporate and state media, to consolidate their state-within-state position, such as the military. This is clear in the message of the Chairman about the closure, in which he said that the problem with EI is that it represents the interests of a limited ideological group of people and that this is not how journalism functions. This is the political depth to the economic argument.

When you talk about economic losses in journalism, every newspaper and television channel in Egypt is losing money. What is at stake is this: What is it that makes a businessman still attached to burning money on an organisation? It is not financial returns. It’s something else and it relates to accumulating power needed for the business to thrive in our context. When that power wasn’t available, they lost interest in EI.

Mia: EI was strongly ideologically positioned, but most striking was the belief that one’s own position must be transparent within the discussion. That in itself is threatening because it implicates the institution quite strongly.

Lina: That’s interesting because I was always keen to speak of ideology as a limitation to imagination with my team. We have a position, and we are conscious of it, and that actually is part of the practice we talk about [in The Triumph of Practice]. For example, news of deaths on a road accident cannot stand alone unless it links to other deaths on road accidents and points to state failure. That’s journalism with a position. But when the Chairman was talking about ideology, he was using it as a tactic of offence; referring to some classical leftist ideology that makes us partisan and less engaging. As someone who comes from the old regime, it’s normal for him to see things in these binaries.

I’m not even sure to what extent what we’re doing is effective in the current moment, but I definitely know that if we don’t exist there would be a crack in the overall narrative of what happened in the aftermath of Morsi’s ouster and the ensuing violence and crackdown on political dissent

Mia: So in what way is Mada Masr’s birth a specific response to this, and how is it better equipped to deal with it now?

Lina: There’s nothing better at providing a raison d’être for what we do than the context in which we were born. I take a lot of pride in the idea of starting on June 30th 2013, [the anniversary of the beginning of Mohamed Morsi’s presidency, and the date of major protests that contributed to his ouster]. I started it then for sheer psychological reasons, and not for grand political aims of reporting this important event. Even in the apocalyptic lead-up to this date we felt that it was going to be something transformative. It would have been existentially problematic for us to have stayed behind, or be assisting other news organisations, or watching the news on television. We take refuge in journalism as a prism through which we engage with events politically. So it was a therapeutic thing more than anything else.

Rationally it was difficult to begin on that date – the website was far from complete, nothing was working perfectly, but I just knew that I wanted everyone to be out in the street and operating as they would normally operate if they were part of EI. Our journalists shone, but also it proved to be an important political tactic.

We are seeing an extreme polarisation in the narrative and in this process, information actually becomes a casualty. It is a perfect moment for a journalist, in the classical sense of the word, to thrive, especially that politically it’s been hard for all of us to take a position on what happens. We were even shying away from engaging with the ‘coup versus revolution’ disputes and so on. We were much more invested in collecting facts and obsessively documenting what would become a deeply difficult juncture in our history and our story of revolution.

So I’m not even sure to what extent what we’re doing is effective in the current moment, but I definitely know that if we don’t exist there would be a crack in the overall narrative of what happened in the aftermath of Morsi’s ouster and the ensuing violence and crackdown on political dissent, which is defined otherwise by whoever becomes the winner at the end.

But is journalism a science or is it an art?…Mada can roughly translate as range, but it’s also the spot in the ring where the ring stone is placed, a symbol of taking a position

Mia: After the end of EI as we know it, I know the future Mada Masr team took a retreat to assess the past and envision your future as a new news organisation. Can you tell me about that?

Lina: When we engaged in the re-envisioning of Mada Masr, we were anxious to continue what we started at EI. There was a process of reflecting on failures, dreams, and things that did not happen, but it was seen as a continuation of an interrupted process. It’s a practice that became homeless, we can speak about the process of relocating it to a new home, rather than changing the practice itself.

When we started we had to figure out what kind of institution would best accommodate our work. We hadn’t registered yet, we didn’t have any investors yet; what we had was people working endlessly without accreditation – everything that journalism isn’t supposed to do, and all things that we started addressing later.

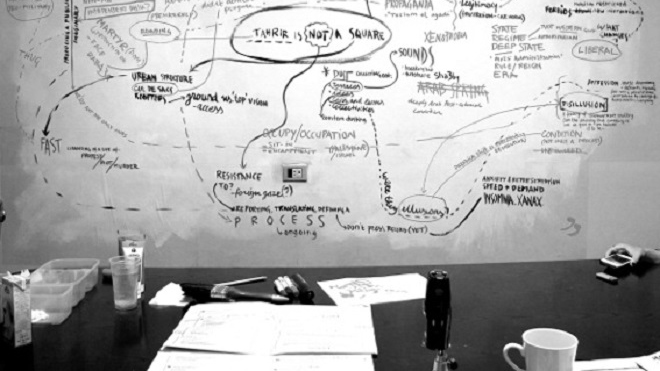

Instead, our journalistic practice had activated the process of building the institution: everything from naming it and the failure in doing so collectively. We had those very long brainstorming sessions and plenty of flipcharts were burned, and so, quickly the naming process became a practice. It was nailed down to this kind of discussion: ‘This is not an art space, this is a newspaper, we should call it something straightforward.’ Somebody responded saying: ‘But is journalism a science or is it an art?’ and that was an ongoing thread. Of course in the process, the name became the casualty, but the conversation itself was a reflection on praxis. Mada can roughly translate as range, but it’s also the spot in the ring where the ring stone is placed, a symbol of taking a position.

Mia: Given what you’ve just told me about the homelessness of your practice after the closure of EI, could you then say the home you found was June 30th, rather than a particular institution called Mada? Is that too much of an assertion?

Lina: As we speak, June 30th is unfolding, and with it our positions. Right now we are in the process of unfolding as a group with no-position. [Mada Masr journalist] Sarah Carr tried to get into this a bit (On Sheep and Infidels, July 8th, 2013). Now how can you have no position and remain engaged? This was the formative question of June 30th, which kick-started our new existence as Mada Masr. So the 30th June moment was the doorstep, maybe not the home though. One of my thoughts around this is that this is a moment where we simply need to remain in our marginalities and use them as a site of empowerment and alternative arrangement.

Mia: You’re referring to Back to the Margins, which Mada Masr co-published with Jadaliyya.com. In this article, you self-identify as not being with any of the prevalent moods of the moment – whether pro-military, feloul (remnants of the Mubarak regime), or pro-Morsi/Muslim Brotherhood – and recognise this as a:

Kafkaesque instance where a metamorphosis of self or revolution was unfolding. It is either we have become the counter-revolutionaries, or the revolution has become the counter-revolution. But beyond the insanity and the psychological entrapment of a revolution making a full circle to return to its point of inception, there may be a way out. And it is reclaiming our initial position prior to the revolution.

[…]We remain who we are, we continue to do what we do, but operate from our predetermined and archetypal marginality. But we still hold on to the thought that a revolution was born from this marginality.

Lina: June 30th is all about that. It’s an emergent event and it’s very hard to have a clear position right now, so while all these questions are looming in our minds, we sent the analysis to the backseat and focused on the event as it is happening. What this event calls for now is documentation in its most systematic, obsessive, and even boring form because that is what’s becoming scarce, a casualty alongside the other casualties. In that sense, June 30th is a doorstep to the new home of this practice, namely being able to acknowledge that it is not a moment of political clarity, but one of responsibility toward an archive that would otherwise be absent. Take yesterday [June 7th, when tens of Muslim Brotherhood supporters were killed in clashes with the military in front of an army club]; nobody in the local media was talking to eyewitnesses. Nobody was doing that at all, when it is supposed to be the most intuitive aspect of the act of documentation. The act of documenting was disrupted and this is where we came in.

We obviously didn’t expect the events of Morsi’s ouster to unfold this way, nor did we anticipate our position to be so confused and conflicted. This documentary practice had always been there somehow but it began to shine in our minds because we were consistently doing something decisively different in this context of polarization. In other words, the measure of self-reflection and acknowledgement of uncertainty was key to defining the way ahead.

Mia: Speaking about other specific problems in the media, such as censorship and more particularly, self-censorship. A cumulative psychological climate is produced through all the tactics that induce self-censorship: what sort of subjectivity is this, and how do you resist it within Mada?

Lina: In circumstances like ours I don’t particularly like the straight-up demonization of any act of self-censorship. In a context like the Hosni Mubarak dictatorship, it becomes a negotiation process with survival being ultimately the objective; at the risk of romanticizing it, it becomes a site of creativity. One of my references here is a series of magazine works by Iranian artists Farhad Moshiri and Shirin Aliabadi called Freedom Is Boring, Censorship Is Fun, where they play on the irony between the censored image and the written text – it’s an interesting project. That said, I think what’s at stake is consciousness.

The unconscious and sometimes conscious internalization of censorship translates itself into institutional practice and personal editorial practice. So one of the things we try to activate consciously and consistently in our practice is the self-questioning. I do not think this can be an individual exercise. If it becomes indistinguishable from the self, you need the outside support to flag an act of censorship or self-censorship. There is stuff we’ve inherited because we were born and have emerged out of this system, and we’ve been parasites within it so you cannot pretend that you’ve come out completely intact and emancipated. At the same time, by activating and reactivating your awareness of this you may resist what would be tendencies for censorship, general worries, or paranoia.

I must say that a good percentage of paranoia is institutionally constructed. I really feel emancipated now that I ‘am’ the institution in a sense. We haven’t been out there for long enough to explain why I feel this way, but the current moment we’re living through is a good example. There is active control from the military right now of the narrative of the events that is coming out of both state media and privately owned media: Youtube videos, eyewitness accounts, articles have all been taken out. At EI, even though no-one would come and tell me to remove things directly, I would personally worry a little in the inside to publish contentious articles. And I would start treating the act of producing some of this dissident content as an act of bravery. Right now it’s just sort of natural. You just produce this stuff and it’s your normal practice. So acts aside, I think it is important to dig into the “sentiment” that roots self-censorship, understand how much of it is institutionally constructed and how much of it is personal.

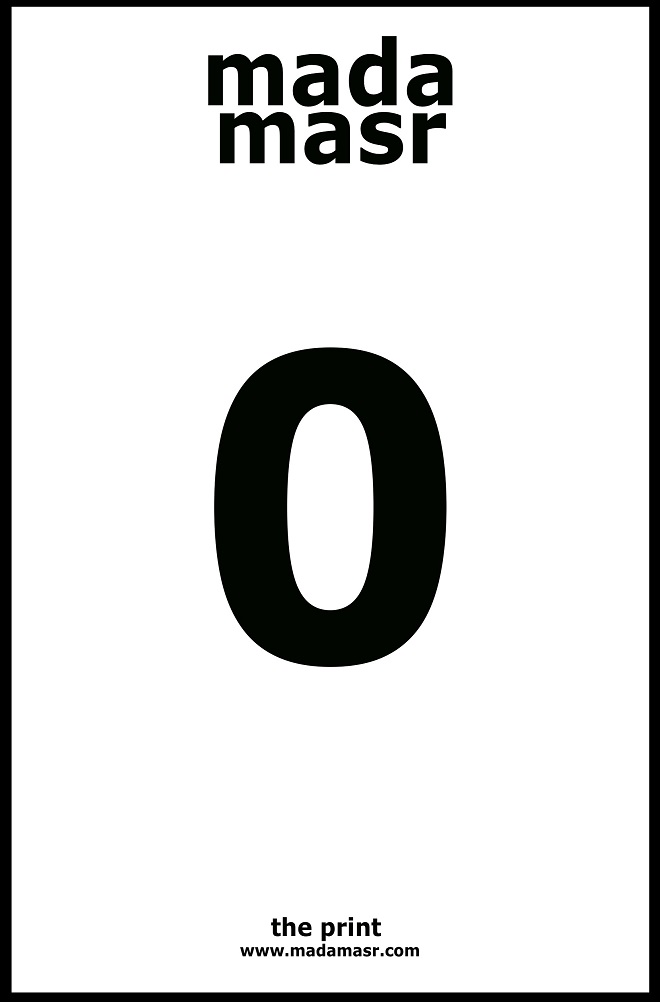

Cover of Mada Masr The Print, issue 0, published in September 2013. Image courtesy of the artists and Beirut.

Mia: I heard recently that Alexandra Stock, previously a curator at Townhouse Gallery, referred to EI as Cairo’s ‘third art space’ [after the two dominant ones at that moment, Townhouse and CIC]. Notwithstanding the obvious fact that there’s some really specific differences between art and journalism, why do you think she said this? What does it mean to be compared to an art institution? Is it the connection to Take To The Sea, the multidisciplinary research group under which you personally form your artistic practice?

Lina: I have been very conscious about activating the artistic sense in everyone’s practice as journalists, in the sense that journalism is not just about documenting or covering what’s there, but it’s also about proposing alternative possibilities at times. This is where I feel there’s a strong intersection, and it is an ambition of our practice in general. Everyone at Mada likes to joke about the words I use a lot, and how I talk about ‘making propositions’ and ‘hacking discourses’ all the time, but it’s also the type of jargon I would use in a conversation with Nida [Ghouse] and Laura [Cugusi] in Take To The Sea.

So it’s this aspect of the ambition behind the practice: the practice of telling, the practice of writing, the practice of narrating; beyond documenting what’s there, especially when mainstream journalism has chosen reductionism as its main mechanism of mediation. I think it’s transcending that basic notion of ‘truth speaking to power’, and you know, ‘being out there’, and ‘reporting with honesty’. All of that is there, but there is a further ambition for me here, which is to let people think about another possibility out there. So for instance we feature a community living in a low income housing informally paving a road for itself that would link it to the highway in order to cut on transportation cost and hurdles, parallel to writing about the woes of low income housing. The possibilities are not always pronounced, they may be subtle but we are set to unearth them as we go. In fact, this is the condition of Mada’s becoming, from naming it to shaping its content.

Mia: And this is where I think the practice of art institutions, Mada Masr, and the kind of protests we saw on January 25th, 2011, all relate: it concerns a radical form of psychological habit breaking.

Lina: I think we have to be careful with being too conscious of this art practice in our thinking because it can also become a bit forced. But one thing in relation to your question that is at the intersection of art, our work in Mada, and Egypt today is the emotional register of relating to the events around us. At some point psychosis and madness became ways with which we submit to understanding the evolution of the masses. This frantic pointing of lasers at military jets, taking pictures next to tanks are all essentially part of some collective madness or at least going out of the ordinary, and that has to be acknowledged. I think that ignoring these phenomena is actually an impediment to mediating how things are happening. And so in Mada I have increasingly encouraged people to actually write with emotion. Either their own, or the emotion they witness while they cover events, even in their regular reports. It doesn’t have to be a first-hand account, it doesn’t need to be separated as ‘this is an emotional piece’ and you should consume it that way. But even as they actually cover the events in a straightforward manner, mediating this mixed emotional baggage with which events are produced and consumed, becomes something of an artistic practice. It also breaks the journalism code, it cracks it completely in fact, but it’s also like that uncharted territory that you have to enter when you are increasingly dissatisfied with the fixed narrative.

To give you a more concrete example, look at how people are increasingly moving to social media from mainstream media. Social media offers emotional spaces of expression. It’s a space where people can afford to tell the event with an emotive ingredient. This is something the mainstream media shies away from, it’s considered a faux pas. It’s an interesting thing to learn from social media – usually we’re thinking of its decentralization, its non-institutionalism, but there’s also a heightened ability to express with emotion and hence produce a sense of engagement, affinity, empathy, or the opposite. This is where journalism can expand, but also art and the whole 25th January imaginary. It’s not one story. There is no one way of telling it. It’s filled with complexity and confusions that are produced by the way our emotions permeate the unfolding of events. And as we operate, we need to acknowledge that it continues to unsettle us; that what we took for granted, such as the prowess of the state, is now eternally shaken.